I read a lot. I read a lot of things I like. I read a lot of things I think are very clever and smart. I read a lot of things that I admire deeply and continuously.

I very rarely read something and think, “Jesus, I wish I’d written that.”

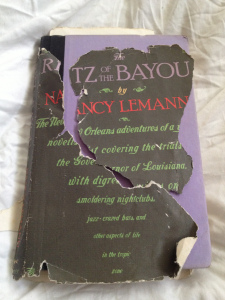

That’s how I feel about Ritz of the Bayou.

I was first introduced to Nancy Lemann via my friend Snowden‘s great essay about her fictional work, Lives of the Saints, which I plan to reread and profile at a later date, since it is also a staggering, unheralded work of wit and intellect. The way this lady writes sounds a lot like the way that I think I talk, and it seems like perhaps our biographies overlap significantly, if, indeed, life imitates art and vice versa.

Onto Ritz.

It’s…creative non-fiction, I suppose. That’s a term I don’t like because it implies that the academic, serious book must always be dull, that research and extensive background is inherently boring, and that non-fiction writers are humorless saps devoted to obscure and facts no one cares about in the slightest. If I could tell you about all the interesting twists and turns I’ve seen non-fiction take, we’d be here until the end of the next Clinton’s administration; I find the term to be as dismissive and insulting as “black writer” or “women’s interest.” And anyway, she hardly sticks to the facts, but everyone knows there can be truth without those.

But creative non-fiction it is. The story, as it exists, tells of the racketeering trial of Louisiana governor Edwin Edwards in the mid-80s and the coterie of attorneys, journalists, bailiffs, etc., that attend to it. She borrows heavily from the style of Kentuckian and genius Hunter Thompson, which is to say it’s a bizarre, heady, colorful, semi-confessional pandemonium spread out over a couple hundred pages. This is, in fact, the only way to adequately consider Southern politics.

Her one-liners, her coy self-reference to beaux past and present, her ability to cut right to the heart of the duality inherent of Southerness: Ritz borders on being a mirror to a culture that would rather be angry than bored, that pretends to be romantic but is really cynical. If someone from Minneapolis wrote this book, I would be livid about the overgeneralizations, the cliches, and the zealousness with which she pursues both, but she isn’t, so it’s fine. The South, as I mentioned, is like your trashy cousin. I’ll hyperbolize and trash talk all I want, but God help you if you agree with me.

There are two things that I hold dear about Ritz, outside the joy of it, the comedy of the Southern political machine. Firstly, she considers the way that impeachment, and corruption more broadly, changes lives. Sure, it changes the accused, but who cares? It drags bureau chiefs out to obscure towns, it fills the public with doubt, it’s a king-maker for the right attorney, and it’s always a veritable circus that provides almost limitless gossip, endless hours of entertainment.

I love that.

Do we see Edwin on trial? Of course. But you could have traded him out for perhaps any governor of any Southern state in the last century: bawdy, flamboyant, ineffective, shrewd, good-ole-boy, the list goes on. Like I said, it’s a culture that picks mad over bored any day of the week.

The other thing, and it’s topical now, is how she talks about the heat. I love the heat of the Deep South: it’s unifying. No one really thinks you’re going to work during the period of, say, 10 July-20 August. There’s no expectation that you’ll wear a suit to work (or keep the whole of it on). Everything moves slowly, and it imbues each and ever action with a sense and depth of meaning that is completely, utterly invented. Yet the actions you take in June seem so much more purposeful, so much more durable, than anything you do in February. Lehmann talks incessantly of the sweltering, merciless heat, and of sweating, and of ice water, and of the stupid, unforgivable things people do in the heat. It’s 102 as I write this, and I’m considering what the next eight to ten weeks may hold; it’s not pretty.

I steadfastly encourage you to read this; it’s funny, it’s easy, but it’s smart, and it’s incisive. If you like me, you’ll like this. I’m giving myself too much credit, but then again, it’s hot out.

Next week, I’m reading this. Please join me.