Happy first book of 2014, buddies! As promised, we get to talk about Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walters, a book I would not have read were it not for very, very limited options in the airport bookshop.

I’m glad they didn’t have much, because I enjoyed reading this, and I wouldn’t have picked it up otherwise! The design of the cover does it no favors, and I think “Jess Walter” sounds like a Confessions of a Shopaholic kind of author name, right? I know I’m being a big jerk, and I guess I forgot about The Financial Lives of Poets or his myriad pieces I’ve read in magazines and liked. Oops.

The story is about a man who keeps an tiny inn on the coast of Italy and the glamorous actress who visits there in the 1960s. No, wait, the book is about Richard Burton and the Donner Party. Ah, no, I’m sorry, it’s about modern day Los Angeles and a disillusioned young woman working in film as a glorified assistant. Forgive me, I forgot- it’s about her boss. Maybe it’s about her boyfriend, or an alcoholic Spalding Gray knockoff. It’s about all of them, together and apart, at once and over time. The word “high-wire” comes to mind when describing the feeling of the novel, and the whole thing feels like a movie from “go.” While reading it (and I tore through like a woman possessed), I felt like I could cue the suspenseful music here or fade to black there; Beautiful Ruins walks a fine line between hokey and workin’ it with play-within-a-play-as-device, and it almost completely succeeds throughout. Dude’s a great storyteller.

I love an ensemble cast, as I mentioned when we read Bel Canto, but I often struggle with feeling like the characters are as round and dynamic as I’d like, and I frequently feel as though I don’t get closure with all of them in the ways I’d like. Beautiful Ruins succeeds at fifty percent of these. By the last pages of the book, I had a great sense of what everyone was about, and could reasonably guess who was a cornflake person and who was a Frosted Flake person, which of these people I’d call to get me from jail, and if any of the characters were the sorts who pronounce it “Tar-ZHAY.” By the same token, I did feel like I got rushed out of a couple rooms in an effort to close all the doors on the way out of the house. I wanted to know more about the outcome of the aforementioned disillusioned assistant, and I felt a little confused about the ultimate motivations of her boss. These were both great characters, and I wanted to know more, which I never will. The outcome of Richard Burton, well, that one is available on Wikipedia. (Spoiler alert: he dies.)

A game I often like to play with pieces of real-enough fiction is this: I ask myself if I can assume that a character can name the principle characters in Saved By the Bell. Not that specifically, but I very often wonder if the world my characters are inhabiting has already upgraded to iOS whatever, or if Barack Obama is president, or if they get their oil changed at JiffyLube. It doesn’t really matter, I suppose, but it’s kind of fun to think about, in the way that Donnie Darko blew your mind in 10th grade (you’re a liar if you say it didn’t.). Beautiful Ruins is a rare piece of art that I feel like I could answer that about (another is Sherlock on BBC, if you were wondering). I have no idea if Harry Potter knows about The DaVinci Code but I am damn sure who is a Verizon customer and who is on Sprint in this book. Jess Walters created a fictional, almost-real world that is both completely fantastical and tight as a drum; if it weren’t for the fact that most of these people don’t exist and that the story is so wow, I feel like I could step right in to it, wearing my Gap jeans, joking in Doge, and not really draw much attention to myself. That’s pretty amazing, when you think about it.

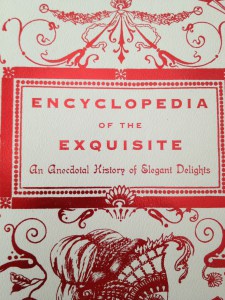

So, have you read this? What did you think? I heard from a reader who loved it infinitely more than his other work, and made a suggestion for a future book club herself (coming soon, miss!). Next week, I’m finishing this, which I’ve been meaning to do for a long time. Please join me! I’d be delighted.