If you haven’t heard, the South Carolina legislature is trying to slash the College of Charleston’s book budget because they’re assigning gay propaganda. Every year, the College, conveniently located a eight blocks from my house (hi Miles [my upstairs neighbor and C of C junior]!), gives every member of the freshman class a book to read together. It’s just a nice thing they do. I think UVA did this too, but I can’t remember, so impactful was their choice. The book this year was Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, which I borrowed from a buddy and read in solidarity. Since I live and vote in this state, and thus pay these guys’ salaries, I wanted to see why they had their panties in a twist.

Fun Home tells the story of Alison Bechdel: a girl/woman from a small town in Pennsylvania who grows up, goes to college, and figures out she’s gay and her dad is, too. Her parents are eccentric, isolated, and artistic, and incidentally own the town funeral home. They live in a house filled with books and antiques and flowers and art, but very little warmth. Almost immediately upon her coming out to her family, her father sort of comes out to her, then kills himself (probably? hard to say). That premise alone was enough to get me to pick it up, plus I was vaguely aware of Alison Bechdel as the creator of her eponymous test. As you may know, I love both small town freaks and litmus tests, so this seemed great. Add the intrigue of Palmetto State legislative scandal and some truly outstanding illustrations and you have a recipe for success.

So I’m reading it, right? And I’m trying to figure out why everyone is so upset, other than the fact that Alison Bechdel is a lesbian, which was mostly background information for the first third or so of the book. She’s just a gay person, moving around in the world. As the book presses forward, I can sort of kind of understand why people might be a little upset about it?

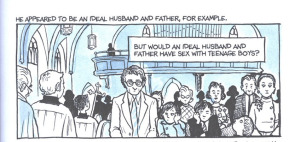

To be clear: this is a book for adults. It deals with sexuality in a straightforward, matter-of-fact way that wouldn’t be appropriate for a six-year-old. Some of the sexuality is behavior that society roundly and rightly condemns (spoiler: her dad is having sex with underage boys), and a lot of it is stuff you just wouldn’t want to be seen reading at work or family outing since it’s a little graphic (spoiler two: I read this at work on my lunch break and three people complimented my book choice).

That said, Fun Home isn’t exactly a manifesto about LGBT issues or some kind of “recruiting tool” or even erotica. It’s a book with some gay people in it. It’s replete with the kind of information every eighteen-year-old has, regardless of their orientation. Last I checked, a college education was about being presented with opinions and viewpoints that challenge your own, not finding a couple thousand other people who also want to play Settlers of Catan and binge on Natural High Life. But I digress.

The thing about Fun Home that most interested me was the fact that Bechdel is coming to terms with the fact that her parents are human, which is one of the hardest things in young adulthood (at least, I hope that’s when it happens. You shouldn’t be faced with hardship too young, nor should you be delusional through your middle age). She loves her dad, but realizes he’s lying to her mom, possibly/probably/almost certainly grooming teenage boys and taking advantage of them if not worse, and possibly exposing them to danger in more than one instance. Those are really, really bad flaws, big accusations to hurl at someone you love. It’s hard to see your parents as people with their own problems and faults, rather than the all-powerful Mom and Dad, and she has a particularly tough row to hoe in that regard. The Bechdel of Fun Home seemed lonely in these realizations, and it made me consider that this is a struggle everyone has, though everyone thinks they are the first and only person ever to do struggle thus. Add to this the fact that her dad kills himself after learning her truth and revealing his own and you’ve got a lot to work through in a couple hundred pages. A careful archivist of her own life, she consults letters and diaries and photos and newspaper clippings and obituaries and church bulletins as she pieces together everything she knows about herself and the man she thought she knew but perhaps did not. Bechdel describes her father and the world he inhabits so clearly that he felt like someone I could know, that their house was one I had visited. It’s a garrulous kind of book, and the language is rich and evocative. Reader, beware: Alison Bechdel knows a lot of 50 cent words and trots out many of them for your benefit.

I learned she later drew/wrote a book examining her relationship with her mom, but her brother seemed like he almost wasn’t there; the rest of the family felt something like set dressing in the more dynamic drama of the father/daughter relationship. I wondered how her brother dealt with the upheaval of their family life, if they talked about it, or if they did. I wanted to know more about what her mother knew all those years, and how she compartmentalized or if she did. I know books can’t be all things to all people, but at the end, I wasn’t even sure what her brother’s name was or his age relative to hers. I had a clearer picture of her mother, but not as much as I felt she deserved, even within the father-focused narrative.

This seems to be a book a lot of people have read and I’d like to hear what your thoughts were. There was a lot to digest in this compact volume- I haven’t even scratched the surface on the art and the colors and those choices!- and if you haven’t read it, I encourage you to do so. Not all meaningful, thought-provoking books come in Remembrance of Things Past-sized covers.

Next week, I’m reading this. Join me!